Food and tradition are tightly intertwined where I come from. Many of the most loved Maharashtrian dishes are synonymous with a festival or event of some kind. Take ‘shevayacha bhat’ शेवयाचा भात, for example. This delicately sweet vermicelli doused in milk and ghee is customary at pre-wedding family parties called ‘kelvan’ केळवण. An age-old delicacy so pleasant and personal, that it became a mandatory part of the kelvan ceremony. I say personal because the vermicelli is traditionally hand-rolled and sun-dried by the matriarchs as a favourite summer pastime. It’s a gift, a cherished memory, a token of love from the bride’s family to take away to her new home. And that’s why shevayacha bhat has a personal touch to it.

What is shevaya and what is shevayacha bhat?

‘Shevaya’ in Marathi means vermicelli. And ‘shevayacha bhat’ is simply a term for the way the vermicelli is cooked and served. The term is akin to steamed or boiled rice we call ‘bhat’ in Marathi. Except in this case the ‘bhat’ is that of steamed or boiled vermicelli.

So shevayacha bhat is a boiled semolina vermicelli dish that’s served steaming hot doused in milk, drizzled with ghee and sweetened with sugar or jaggery. The traditional recipe calls for making your own vermicelli. The gossamer thin vermicelli threads (called shevaya) are boiled in water until cooked. Then served piping hot with milk, ghee and sugar.

Is shevaya the Indian pasta?

Shevaya has much in common with pasta, being made with a dough of wheat flour and semolina and then extruded into long strands which are then dried for storage. That’s why I often translate it as ‘vermicelli’, a type of pasta. India is not exactly famous for its pasta but the shevaya is made with as much love and care as an Italian nonna would give to the task of hand-making orecchiette or ravioli.

How to make shevaya at home?

Living in the UK, it’s not every day that I get to eat homemade vermicelli and milk pudding, we call shevayacha bhat. I am only an overnight trip away from India though, where I can enjoy my Mum’s handmade shevaya. Luckily, when I visited recently, she still had a small stash of her handmade vermicelli left, so I took no time to pack some in my suitcase.

Thin strands of wheat and semolina flour dough are extruded using a special tool called a ‘sorya’ सोर्या and sun-dried to keep throughout the year. This was one of the unspoken obligatory summer chores at my parents’ that everyone in the family had to partake in once a year.

Mum would rinse wheat grains and after drying them on a cloth for a few minutes, would wrap them in a tightly knotted cloth for a day. The next day she’d visit a local mill. Several rounds of sifting and shaking in a ‘sup’ (pronounced ‘soup’) would be called for. For the uninitiated, a ‘sup’ is a special tray-like wicker work contraption that helps separate flakes and husks from grains, lentils and peanuts etc. The milled flour would be sifted to separate coarse semolina and husk from fine plain flour (all-purpose flour or maida). Semolina was extracted by shaking it in the sup separately. The husk is blown away and discarded. A semolina and plain flour dough would be prepared and left to rest for a couple of hours.

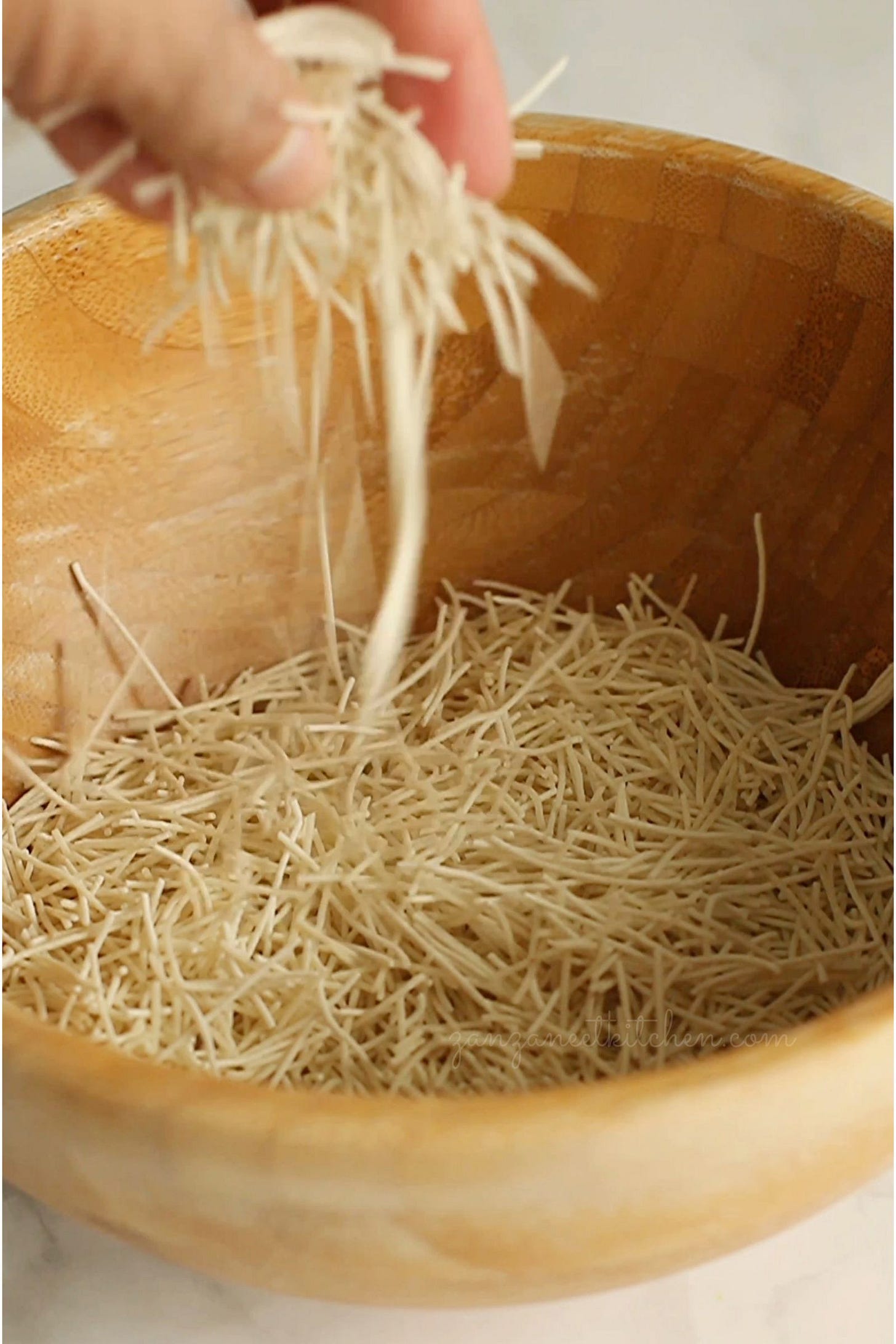

Then the family activity of passing the dough through the sorya extruder would begin. I’d sit atop a sorya fitted table. My job was to rotate the handle as Mum stuffed the dough into the sorya. Sister would collect the resultant thin strands dropping down over a flipped wicker basket. Brother and Dad would take turns transporting the vermicelli-covered baskets to the terrace for sun drying. The strong Indian sun would dry the vermicelli in just a few hours. But Mum would leave them out there until dusk. The strands of wheat and semolina vermicelli would be carefully stashed in a tall lidded brass container for use when needed.

While my Mum used a sorya to extract vermicelli, both my grandmothers would opt for a flat wooden board to hand roll the dough. The strands would be collected and sun-dried much the same way as described earlier. Needless to say, the art of hand-rolling each strand is a dying one.

These days most people in India will use a less laborious method. It simply involves making a dough with shop-bought semolina and wheat flour and passing it through a chakli maker but with a vermicelli die in place. The fastest, most reliable option though is to cook shevayacha bhat using ready-made vermicelli. My Mum sometimes buys it from a friend who makes and sells it at home.

Childhood memories

Shevayacha bhat for me is reminiscent of pre-wedding soirées where newly-weds-to-be are invited round for a family ‘kelvan’ meal and guess what’s on the menu? ‘Shevayacha bhat ani aamras’ (vermicelli with mango pulp). My memories of shevayacha bhat date back to the time I would spend summer holidays at my ancestral home in India. Summer weddings were quite common at the time. I’d happily join either the bride or groom’s cohort and savour the humble vermicelli boiled, strained and served with copious amounts of ghee and sugar. When in season mangoes would make a welcome appearance on the menu (as aamras) and at other times it would just be served with fresh milk.

My riff on the classic shevayacha bhat

I was lucky enough to be given some handmade shevaya by my Mum on my recent trip back home to India. I’m not planning a wedding for anyone but that doesn’t stop me cooking up a few portions of these precious slender threads.

My recipe is a riff on the classic technique. Instead of boiling the vermicelli in plenty of water, straining and then serving with ghee and a generous spoonful of sugar, I first fry the vermicelli in ghee and cook in just enough water. Finally, a dash of sugar and cardamom is added for flavour. I serve it with dried cranberries and a dusting of nutmeg and nourishing oat milk. It makes for a lovely vermicelli porridge kind of breakfast on a dreary day. I need no excuse to savour my Mum’s hug in a bowl. My family enjoy it for breakfast as well and all agree that it’s a major upgrade from toast or cereal

Recipe:

Serves 1-2

Ingredients:

100g dry shevaya or vermicelli

400ml hot water

65g or 5 tbsp caster sugar

2 cloves

8 cardamom pods, seeds crushed to a powder

⅛ of a nutmeg

2 tbsp ghee (or sunflower oil, if vegan)

250ml milk (dairy or dairy-free)

1 tbsp dried cranberries

Method:

In a deep pan on a low to medium flame, melt the ghee and toss in the vermicelli. Stir occasionally for a minute so as to not let it turn brown. The colour should change from white to beige and ever so slightly golden.

Tip in the hot water and stir gently for a minute. Add the cloves. Stir in the caster sugar. Cover and cook for 30 seconds.

Add the cardamom. Mix and serve hot. Pour the milk over. Grate the nutmeg over the top. Throw in the dried cranberries and enjoy!

Also try my ‘shevayachi kheer’ aka vermicelli kheer pudding.

This looks and sounds so comforting. I like the idea of a slightly different morning porridge option 👌